Representation, UAVs and the end of indexicality

Drohnen, insbesondere solche, die heute im War on Terror eingesetzt werden, stellen die Frage nach der Bildauswertung in nie dagewesen radikaler Weise. Ein Schlüsselelement ist dabei die pattern analysis, die im Rahmen des data mining die Interpretation gewonnener Daten übernimmt und Entscheidungsgrundlagen für konkrete Handlungen liefert. Daniel Herleth zeichnet in seinem Essay die Entwicklung seit dem Ende des 2. Weltkriegs nach und zeigt die Verbindung fotografischer und politischer Prozesse auf.

In “The Glass Bees”, a science fiction novel by Ernst Jünger from 1957, we follow an applicant to a job interview. The corporation he visits, reads like a mash-up between Apple, Pixar and Toys’R’Us, owned by an enigmatic man named Zapparoni. This is quite remarkable, given the fact that none of these companies existed, when the novel was published. Witnessing the applicant’s encounter with a swarm of robotic bees in Zapparoni’s garden, while waiting for his result, is even more unsettling. As they buzz around, filling the air with a threatening sound, these bees give him the impression of military robots, though they seem to merely collect pollen. The candidate notices that one of these flying technical miracles – “carved from a dull horny substance or from smoky quartz” – seems to observe him, and he assumes that Zapparoni is “now and then following the messages of the Smoky Gray on his television screen.”1Ernst Jünger, The Glass Bees; translated by Louise Bogan and Elisabeth Mayer, New York 1960

This 50-years-old premonition is only now about to become fully realized, and yet the rifts these artificial insects open in our relation towards distant events are quite apparent; today’s smoke-gray artificial bees pose a number of questions, some juridical, some moral or political, but one of their most decisive aspects is their relation towards the image. With drones, a very specific approach towards the photographic image or, more precisely, to representation generally, lifts off into the sky. Hoovering over Iraq, Afghanistan, Pakistan and elsewhere, their visual output is difficult to classify. And despite extensive media coverage of their activities, little consideration goes into the fact that a drone, for the most part, is a flying aerial reconnaissance center, where images are taken, processed and evaluated in real time.

Thus, remaining invisible while registering even the smallest details became the guideline for UAVS [Unmanned Aerial Vehicles], as drones are referred to more technically; they were meant to be a flying gaze without a body, oriented towards the smallest air vehicles with vision: the insects. Before such invisible drones could be built, they were named after them: Firebee was the first drone that was widely deployed, initially during the war in Vietnam.2The Vietcong, less technically potent but not less inventive, had their own way of deploying bees, consisting in a natural bee hive with an implemented firecracker, remote-controlled blown up when a US-patrouille got near. But for the most part of the second half of the last century the task of secretly observing far away events behind enemy lines was executed by reconnaissance satellites and spy planes, circling unseen, or at least at invulnerable heights, over Russia, China, and other nations of the communist block. The imagery they aimed to obtain had not only to be captured secretly, an image taken from kilometers away also had to be understood. The difficulties of analyzing reconnaissance imagery had been discussed earlier3The writer and reconnaissance pilot Antoine de Saint-Exupéry had used the image of the scientist in the laboratory when he reflected on the difficulties of a photo interpreter facing reconnaissance imagery: “One brings back photographs that are analyzed by stereoscope like growing organism under a microscope. Those analyzing your photographic material do the work of a bacteriologist. They seek on the surface of the body (France) the traces of the virus that is destroying it. The enemy forts, depots, convoys show up under the lens like miniscule bacilli. One can die of them.“ Antoine de Saint-Exupéry, Letter to an American; accessed at http://416th.com/exupery.html on March 12, 2014, but not before the end of WWII methodologies emerged that allow for an understanding of the current situation. The Cuban Missile Crisis is a tipping point in this development, taking place before images became digitalized, the approach already bearing a ‘digital signature’.

TRAPEZOIDAL INDICATIONS

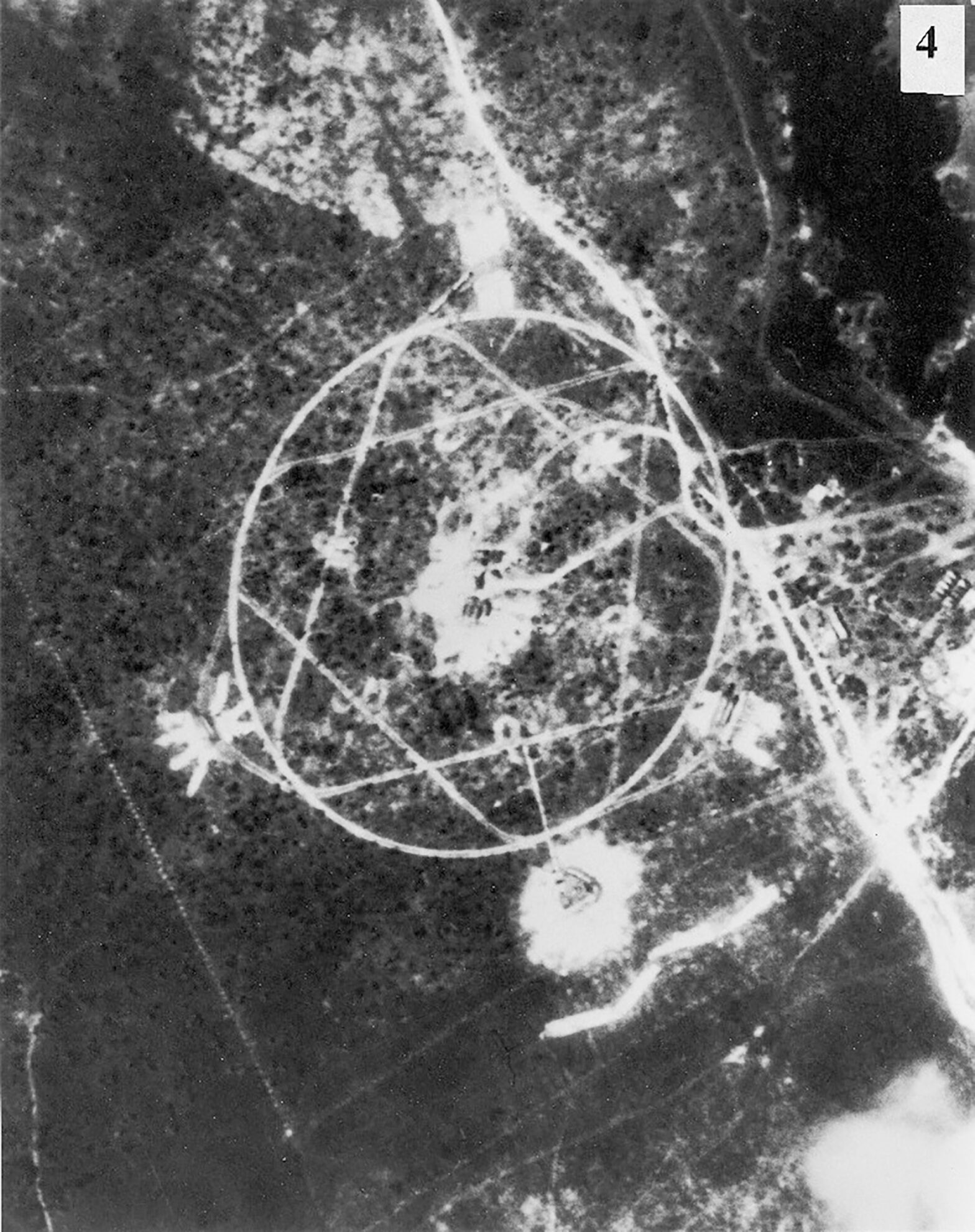

In late September 1962 Colonel John R. Wright studied photographs that had been taken over Cuba a few weeks earlier by a U-2 reconnaissance plane when he noticed a certain pattern among the Russian SA-2 SAM anti-aircraft missiles. The existence of these missiles was known, but the formation they had been set up, the trapezoidal shape they formed, made Wright nervous, as “this pattern was similar to those identified near ballistic-missile launch sites in the Soviet homeland”.4The San Cristobal Trapezoid, John T. Hughes with A. Denis Clift; accessed at https://www.cia.gov/library/center-for-the-study-of-intelligence/kent-csi/vol44no4/html/v44i4a09p_0001.html on March 10, 2014Wright couldn’t exactly see what these images indicated to him, he had to combine them with external data, stemming from other images or other forms of intelligence. It was pattern analysis, a statistical operation that allowed Wright his apprehensions, and the results were orders of magnitude far from an unambiguous fact. The products of new reconnaissance flights were presented on October 16th by General Carter and his photo interpreters in an EXCOMM meeting at the White House, but neither President Kennedy nor the other members could figure out the point. Carter and his team had to tell them what they were “looking at, and some probably weren’t at all certain they were seeing what they were told they were seeing anyway.”5William E. Burrows, Deep Black, New York 1988, p. 120

Robert Kennedy, then Attorney General, remembered this situation quite clear: “Experts… told us that if we looked carefully, we could see that there was a missile base being constructed near San Cristóbal, Cuba. I, for one, had to take their word for it. I examined the pictures carefully, and what I saw appeared to be no more than the clearing of a field for a farm or the basement of a house. I was relieved to hear later that was the same reaction of virtually everyone at the meeting.”6Robert F. Kennedy, Thirteen Days, New York 1969, p. 24 In these moments a crucial shift in the understanding of photographic images occurred: since its invention considered to be the most accurate form of visual representation, photography suddenly did not allow for differentiation between a military site and a farm.

Adlai Stevenson, American ambassador to the UN, had the difficult task of explaining what was in front of everybody’s eyes a week later, on October 25th, when he had to convince the General Assembly that the Russians were indeed installing ICBMS [Intercontinental Ballistic Missiles] in Cuba. Stevenson brought the reconnaissance images with him to the assembly and performed the task of a photo interpreter, going through picture by picture. He even brought photo analysts along, prepared for further explanations afterwards.7”These photographs, as I say, are available to members for detailed examination in the Trusteeship Council room following this meeting. There I will have one of my aides who will gladly explain them to you in such detail as you may require.“ Stevenson’s full speech at: http://en.wikisource.org/wiki/Cuban_Missile_Crisis_speech_to_the_United_Nations_Security_Council accessed December 8, 2012 While Stevenson was successfully presenting his photographs, Colin Powell was not when he spoke at the UN more than forty years later, on February 5th, 2003, even though he knew about the problematics: ”Let me say a word about satellite images before I show a couple. The photos that I am about to show you are sometimes hard for the average person to interpret, hard for me. The painstaking work of photo analysis takes experts with years and years of experience, poring for hours and hours over light The Cuban Crisis took its course, but even if the motto of the Air Force squadron that executed the following low-level reconnaissance missions was Voir c’est savoir, human vision alone wasn’t capable of perceiving the demanded information any longer. Photographs had entered a stage where simply looking at them or showing them wasn’t enough, they needed additional information coming from outside the image to ascribe the image a certain meaning. Far from understanding the photograph as direct and obvious representation, that might only be restricted by what it didn’t show – by ways of framing, timing, perspective, position, etc. – here the notion is totally different: the image itself is very abstract, what it shows, what one can see and what it contains might be totally different things. Photographs had become obscure containers, black boxes in need of something or somebody to open them and extract or read out what was immersed under their surface. Significantly, crateology was the ‘science’ of identifying the contents of Soviet shipments to the Island of Cuba carried out by the CIA.

Even before digitalization, photographs got a depth, a materiality, that was no longer minor to the surface allowing the later transition from looking at to working with a photo. Photographs became subjects of interrogation, raw material for processes that mine for concealed information. And just as the capabilities of human vision had been limited, the results of analysis fell in a different order, as they were only indicators, or better: symptoms. Photo interpretation meant longing for the unconscious of the image: “Photo interpretation has to do with making assumptions based on association and orders of probability.”8William E. Burrows, Deep Black, New York 1988, p. 108 While the discourse around the photographic image had been (and still was) oriented towards indexicality, orders of probability and associative procedures definitely stressed this notion. But things developed even further in that direction: during the 70s, the National Photographic Interpretation Center (NPIC) introduced Digital Image Processing (DIP) as default procedure. There, computational processes made objects visible, that before might have gone unnoticed.9”Photo interpreters who had used their eyes almost exclusively to examine the size and shape of objects, the patterns made by those objects and others near them, as well as the shadows, tones, and shades of light, were supplemented by high-speed digital computers that took the analysis of imagery what, exactly, was in the pictures – far beyond mere ’eyeballing’.” Deep Black, p. 211 These programs already could “sharpen out-of-focus images, build multicolored single images out of several pictures taken in different spectral bands to make certain patterns more obvious, change the amount of contrast between the objects under scrutiny and their backgrounds, extract particular features while diminishing or eliminating their backgrounds altogether, enhance shadows, suppress glint from reflections of the sun, and a great deal more. Radar and infrared imaging used in conjunction with the digital computers would allow objects only partially seen through cloud cover or haze to be reconstructed, and even some targets underground could be defined and highlighted.”10William E. Burrows, Deep Black, p. 211f

Photography’s hegemony was based on two pillars when it came to representation capabilities: first the direct physical linkage from the light-reflecting object to the developed photograph – the indexical aspect. Secondly its resemblance with human vision: the model of linear perspective had held a privileged relationship to representational truth since the renaissance.

Centered around a hole, in linear perspective in a vanishing point, representation crumbles and at the same time the image is guaranteed. It is this imaginary reference pointing towards what is external to the image, that makes sure representation is precisely operating along the model. This vanishing point is mirrored by the blind spot in the eye of the subject of enlightenment, where perception of light is once again bundled together with meaning, where vision and insight are synonymous. Being its technical equivalent, photography made this vision recordable, exchangeable and open for unlimited distribution. The results were a normalization of vision and a relation between the camera and the human eye that had become metonymic.11Jonathan Crary, Techniken des Betrachters, Dresden/Basel 1996, p. 135 Both the gaze of the spectator and the image didn’t need any further examination. With the index an understanding had been established where every interference limited the truth-value-complex embodied in the photograph. This truth was exclusively to be found on the surface of the photograph.

In the Cuban Missile Crisis, the photographic image has lost much of that nimbus, but also its prospective fate was already preconfigured. The image had largely been understood technically, with a calculus, but there were still subjective considerations involved. Additionally, these analog images could only be evaluated hours or days after they had been taken, only to enter a political process upon their content. In such moments, time was an essential factor, and its importance was thriving the development of the first operational digital camera: On January 21, 1977, Jimmy Carter got a set of photographs from CIA director E. Henry Knoche. They were the results of a new project called ‘Keyhole’, whose aim was to take and observe photographs in real-time. The source of these images had been a new type of reconnaissance satellite, the KH 11, that was equipped with a CCD (charge-coupled device)12Basically, a CC D collects radiated particles of energy, including those in the visible part of the light spectrum, by capturing them in an array of tiny receptors, or picture elements, called pixels, which automatically measure their intensity and then send them on their way in orderly rows until they are electronically stacked up to form a kind of mosaic. These ’mosaics’ were the first digital photographs; in the KH 11 already a number of 800 × 800 pixel CC Ds were operating, each spawning image with 640.000 pixels taking photographs. While previous satellites used rolls of analog material to save images and dropped the exposed film in buckets to the earth, the KH 11 sent a digital signal to the intelligence headquarters at Fort Belvoir, outside Washington, where the digital code “was instantly converted into recognizable high-resolution pictures on a screen.”13William E. Burrows, Deep Black, p. 219 The effect on intelligence was considerable, as “they represented the fulfillment of the oldest and most cherished dream of those who ran overhead reconnaissance: that of being able to look down on events happening perhaps halfway around the world and watch them from right up close, virtually as they happened, the way an angel would.”14William E. Burrows, Deep Black, p. 218 But while this algorithmically driven understanding, based on number crunching, is probably hard to compare to the divine, holistic view of an angel, there was another lack: the delay in the possibility to react towards the now real-time image-flow. In todays drones the ‘angel-view’ got the divine power to act immediately. In fact, not only did it tremendously effect intelligence, it was another step towards a totally different understanding of photography: no longer a witness of past events, they now allowed the future to happen. Vision and its recording – a photograph – don’t have a privileged relationship to truth any longer when vision is simply one of the sensors placed around the subjects; a multispectral scanner circling the earth in a spy satellite recording all sorts of wavelengths, most of them outside the frequencies the human eye can incorporate – from ultraviolet and radar to infrared – can hardly figure as an ‘eye’ in the usual sense. Vision and observation, or rather: processing, became separated. Eye and consciousness are no longer aligned but split by thousands of kilometers and encoded and converted multiple times, from optical to electrical, finally crystallizing on a LCD-screen. This signals the end of any metonymic proximity between the eye, the camera, and understanding. There is not just a split between vision and consciousness, but there is no entity: the vision of the drone is first of all a vision without an observer: not that nobody watches its imagery, but there is no defined subject mastering this vision, just a vast network of computers and screens, spread around the globe.

EXECUTIVE SCANNERS

But while during the Cuban Crisis the ‘orders of probability’ extracted out of the images entered a political process investigating into their content, for today’s UAVS this process is not a political one, but an instant algorithmic procedure, executed behind barb-wired fences and classified restrictions. The result is again an order of probability, but more similar to suggestions one is getting from online retailers than the results of negotiations in front of the UN General Assembly. This wasn’t always the case. In the early years of the Afghanistan and Iraq wars drones were mainly used to kill particular individuals who had been followed closely by intelligence on the ground. But soon an additional model appeared, no longer based on intensive intelligence: the so called ‘signature strikes’. These strikes are executed on a ‘pattern of life analysis’, the targets are “groups of men who bear certain signatures, or defining characteristics associated with terrorist activity, but whose identities aren’t known”.15Living Under Drones: Death, Injury, and Trauma to Civilians from US Drone Practices in Pakistan; Stanford School of Law and NYU School of Law, September 2012, p. 12-13 In the words of Steve Kappes, the CIA’s deputy director: “Mr. President, we can see that there are a lot of military-age males down there, men associated with terrorist activity, but we don’t always know who they are.”16Daniel Klaidman, Drones: How Obama Learned to Kill, http://www.thedailybeast.com/newsweek/2012/05/27/drones-the-silent-killers.html accessed 12.12.2012 This proceeding, also referred to as ‘crowd killing’, caused the escalation of drone missions under the Obama administration. In combination with the constant presence of the drones, this pattern analysis renders verdicts out of statistical data, and when a certain degree of probability is obtained, it’ll kill the target. The drones function as a permanently executed type of ‘Rasterfahndung’17Developed in the 70s in Germany as an effort to find members of the RAF , it can be seen as the equivalent to the US shifted approach toward reconnaissance imagery. Both were made possible with the advent of digital information processing and ’number crunching’. (grid search), making peoples lives depending on vague ideas, fed into computers. This has immediate, disturbing consequences: “Drones hover twenty-four hours a day over communities in northwest Pakistan, striking homes, vehicles and public spaces without warning. Their presence terrorizes men, women and children, giving rise to anxiety and psychological trauma among civilian communities. Those living under drones have to face the constant worry that a deadly strike may be fired at any moment and the knowledge that they are powerless to protect themselves. These fears have affected behavior.”18Living Under Drones, p. 80 Seemingly drones often strike when the elders come together to discuss, the most basic form of social life in Pashtun culture. But the fear of attacks not only affected these meetings, but every aspect of social life, with children taken out of school, everybody afraid to go anywhere (because the person next to you, the car or the building might be a target), even collecting the body parts of your family members after a strike or burying them can be deadly. There are no specifics published by the US administration about the nature of the patterns to identify terrorists, but the general outline seems to be that “people in an area of known terrorist activity, or found with a top al-Qaeda operative, are probably up to no good.”19ibid. p. 13 This kind of ‘probability’ is tragic, even though the Times joked, “three guys doing jumping jacks, they think it is a terrorist training camp.“20ibid. p. 13 To limit the numbers of civilians killed by drones the administration labels all military-age males killed in drone strikes as combatants. The statistics have to be tidy, after all.

- 1Ernst Jünger, The Glass Bees; translated by Louise Bogan and Elisabeth Mayer, New York 1960

- 2The Vietcong, less technically potent but not less inventive, had their own way of deploying bees, consisting in a natural bee hive with an implemented firecracker, remote-controlled blown up when a US-patrouille got near.

- 3The writer and reconnaissance pilot Antoine de Saint-Exupéry had used the image of the scientist in the laboratory when he reflected on the difficulties of a photo interpreter facing reconnaissance imagery: “One brings back photographs that are analyzed by stereoscope like growing organism under a microscope. Those analyzing your photographic material do the work of a bacteriologist. They seek on the surface of the body (France) the traces of the virus that is destroying it. The enemy forts, depots, convoys show up under the lens like miniscule bacilli. One can die of them.“ Antoine de Saint-Exupéry, Letter to an American; accessed at http://416th.com/exupery.html on March 12, 2014

- 4The San Cristobal Trapezoid, John T. Hughes with A. Denis Clift; accessed at https://www.cia.gov/library/center-for-the-study-of-intelligence/kent-csi/vol44no4/html/v44i4a09p_0001.html on March 10, 2014

- 5William E. Burrows, Deep Black, New York 1988, p. 120

- 6Robert F. Kennedy, Thirteen Days, New York 1969, p. 24

- 7”These photographs, as I say, are available to members for detailed examination in the Trusteeship Council room following this meeting. There I will have one of my aides who will gladly explain them to you in such detail as you may require.“ Stevenson’s full speech at: http://en.wikisource.org/wiki/Cuban_Missile_Crisis_speech_to_the_United_Nations_Security_Council accessed December 8, 2012 While Stevenson was successfully presenting his photographs, Colin Powell was not when he spoke at the UN more than forty years later, on February 5th, 2003, even though he knew about the problematics: ”Let me say a word about satellite images before I show a couple. The photos that I am about to show you are sometimes hard for the average person to interpret, hard for me. The painstaking work of photo analysis takes experts with years and years of experience, poring for hours and hours over light

- 8William E. Burrows, Deep Black, New York 1988, p. 108

- 9”Photo interpreters who had used their eyes almost exclusively to examine the size and shape of objects, the patterns made by those objects and others near them, as well as the shadows, tones, and shades of light, were supplemented by high-speed digital computers that took the analysis of imagery what, exactly, was in the pictures – far beyond mere ’eyeballing’.” Deep Black, p. 211

- 10William E. Burrows, Deep Black, p. 211f

- 11Jonathan Crary, Techniken des Betrachters, Dresden/Basel 1996, p. 135

- 12Basically, a CC D collects radiated particles of energy, including those in the visible part of the light spectrum, by capturing them in an array of tiny receptors, or picture elements, called pixels, which automatically measure their intensity and then send them on their way in orderly rows until they are electronically stacked up to form a kind of mosaic. These ’mosaics’ were the first digital photographs; in the KH 11 already a number of 800 × 800 pixel CC Ds were operating, each spawning image with 640.000 pixels

- 13William E. Burrows, Deep Black, p. 219

- 14William E. Burrows, Deep Black, p. 218

- 15Living Under Drones: Death, Injury, and Trauma to Civilians from US Drone Practices in Pakistan; Stanford School of Law and NYU School of Law, September 2012, p. 12-13

- 16Daniel Klaidman, Drones: How Obama Learned to Kill, http://www.thedailybeast.com/newsweek/2012/05/27/drones-the-silent-killers.html accessed 12.12.2012

- 17Developed in the 70s in Germany as an effort to find members of the RAF , it can be seen as the equivalent to the US shifted approach toward reconnaissance imagery. Both were made possible with the advent of digital information processing and ’number crunching’.

- 18Living Under Drones, p. 80

- 19ibid. p. 13

- 20ibid. p. 13